The Road to Franklin: An Almost Impossible Task

by Eric A. Jacobson

Originally published in the Battlefield Dispatch Vol. 2 No. 2 Spring 2014 - read the rest of the issue here.

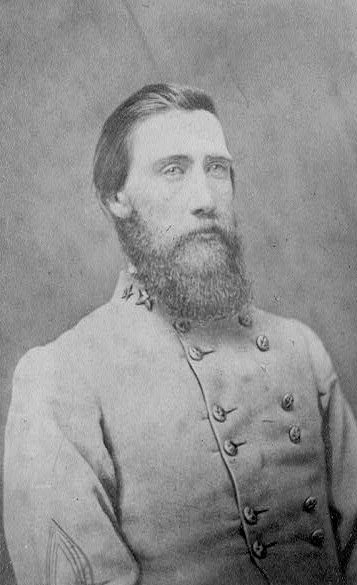

Gen. John Bell Hood. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

When Gen. John Bell Hood took command of the Confederate Army of Tennessee on the night of July 17, 1864, the fate of Atlanta hung in the balance. For two and a half months, Gen. William T. Sherman, in command of three Federal armies operating in concert, had pushed the Southern army from Dalton, Georgia to the gates of Atlanta. Convinced that Gen. Joseph Johnston would not fight for the city, Confederate President Jefferson Davis relieved him and elevated Hood to command. That same night, Secretary of War James A. Seddon very candidly warned the young general, “You are charged with a great trust. You will, I know, test to the utmost your capacities to discharge it. Be wary no less than bold.”

The dismissal of Johnston and appointment of Hood remains today one of the most controversial moves of the entire Civil War. For many decades it has been casually stated, and written, that Davis made a grave error and that Hood was incapable of leading the Rebel army. Such a train of thought is almost exclusively the benefactor of hindsight. In addition, it has been said that there were other more appropriate choices. Perhaps there were. Gen. Dick Taylor or Gen. A. P. Stewart might well have been better selections, but there were others who certainly never even crossed Davis’ mind. That idea that Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne, who had never even commanded a corps in the field, or Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, who was a cavalryman, could have led the Army of Tennessee in mid-1864 ignores the basic facts of promotion. Davis would have never considered the latter for such a level of command, for a variety of reasons, and it is unknown whether anyone other than Hood was ever seriously considered. The truth is, in the summer of 1864, John Bell Hood was as deserving as anyone at that stage. He had risen through the ranks, had performed almost flawlessly on battlefields in both theaters of the war, and Davis wanted someone who would take the fight to Sherman. It is true that Hood had suffered two serious wounds, but his left arm wound had healed quite well, and his right leg amputation, contrary to persistent misconceptions, had also healed and caused him no significant issues beyond a lack of mobility. Unfortunately for Hood and the Army of Tennessee, trying to stop Sherman’s relentless advance would be an almost impossible task.

Hood’s first test as army commander came along the ground south of Peachtree Creek on July 20, when he ordered his troops to attack one of Sherman’s armies - George Henry Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland. The assault, which Hood had planned to commence at 1 p.m., was delayed for three hours, but once it unfolded the fighting soon developed into a series of sledgehammer movements. Gen. William W. Loring’s Division, part of A. P. Stewart’s Corps, succeeded in routing some of Thomas’ troops, but his men were forced to withdraw due to a lack of well-timed support from William Hardee’s Corps. But the delay had thrown the entire Rebel attack out of rhythm. Hood, who was concerned about “demonstrations of the enemy on the right,” had ordered Hardee to shift his troops a half mile to the right. Hardee claimed he was also told to connect with Gen. Benjamin Franklin Cheatham, who was two miles to the east. Instead of advancing to the attack as ordered Hardee lost precious time searching for Cheatham’s left flank. When the assault at last unfolded, one of Hardee’s divisions was repulsed and another, made little progress. He then ordered his other two divisions forward, but soon heard from Hood that enemy troops “were passing and overlapping the extreme right of the army...” Hood requested a division be sent to oppose the threat, and so Hardee forwarded Pat Cleburne’s Division, which was just moments from going into the battle. As a result, Hardee claimed he was left with “no alternative but to give up the attack altogether.” Thomas reported that the fighting continued “till sundown, when the enemy, repulsed at all points, fell back...” Thus Hood’s first attempt to remove the stranglehold on Atlanta ended in failure.

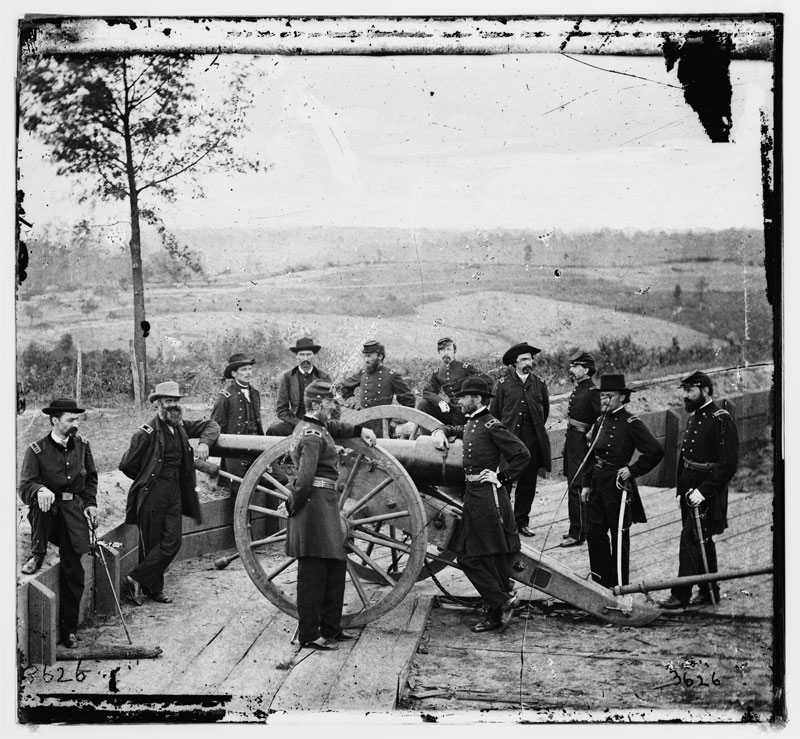

Gen. William T. Sherman, leaning on breach of gun, with staff at Federal Fort No. 7 in Atlanta, 1864. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Meanwhile, James B. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee had become a very serious threat to Hood’s right, but more importantly, to Atlanta. In an effort to try and counter McPherson’s movements, Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry was ordered on July 20 to hold the extreme right of the Rebel army. Wheeler’s line, as it moved south from the Georgia Railroad which ran from Atlanta to Decatur, eventually stretched to Bald Hill, which was about a mile south of the tracks. So while the action south of Peachtree Creek raged, dispatches went back and forth between Southern officers as they desperately tried to shore up the army’s right wing. They were able to hold on, but only because McPherson advanced his troops with excessive caution.

As the action swirled around Bald Hill, plans for another attack were being developed by John Bell Hood. Hood had learned from the cavalry that the left flank of McPherson’s army, which was Sherman’s second largest force, was vulnerable to an attack. To take advantage of the situation, Hood ordered William Hardee’s Corps to move out on the night of July 21 on an eighteen mile march and “completely turn the left” of the enemy army. Once in place, Hardee was to assail McPherson’s left flank and rear. Meanwhile, A. P. Stewart’s Corps was directed to occupy Thomas and prevent him from lending assistance to McPherson or John Schofield’s nearby Army of the Ohio, which was composed solely of the Twenty-Third Corps.

Problems arose immediately. So much time was lost that it was after 3 am before the last of the Rebels were on the road. The men were exhausted, not only from a lack of sleep, but from fighting in the blistering heat all the prior day. It was almost noon before Hardee was finally in position to attack, and the heat, along with the choking humidity, was causing widespread difficulties.

As Hardee’s four weary divisions readied themselves for the attack, one which even at that late hour was still mostly unsuspected, fate reared its head. McPherson’s men were strung out along a line that ran generally from north to south. Meanwhile, early that morning, Gen. Grenville M. Dodge’s Sixteenth Corps had been ordered to move in rear of the army from right to left and extend the left flank. When Hardee’s veteran soldiers came marching and howling out of the dense woods and underbrush, they unexpectedly came face to face with Dodge’s troops. Dodge’s two divisions suddenly found themselves taking on almost half of Hardee’s Corps. The Sixteenth Corps, as Dodge reported, “immediately became hotly engaged...” In what seemed like the blink of an eye, a furious battle had exploded east of Atlanta.

Hood later blamed Hardee for the failure of the attack, but it simply was not possible for Hardee to have known that Dodge and his men would be so fortuitously placed. As it turned out, Cleburne’s Division achieved the only bona fide Confederate success of the day when his three brigades struck the area of McPherson’s line southeast of Bald Hill. His troops flooded the gap that existed between the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Corps, and the battle escalated into a seething fury. The combat was hand-to-hand in many areas, but slowly the gap that Cleburne had hit began to close up as the left flank of the Seventeenth Corps was refused. A Federal officer said, “Men were bayoneted...and officers with their swords fought hand-to-hand with men with bayonets.” Only late in the afternoon were Pat Cleburne’s weary and bloodied troops finally shoved back by a determined Federal counterattack. Moreover, Hood did not order Frank Cheatham into the fray for at least three hours after Hardee launched his assault. When his three divisions, as well as the Georgia Militia, did finally advance, the fighting in that sector was no less brutal or costly. But the lack of cohesive action doomed the Confederates. By about 7 pm, as the battle ground to a close, Hood had little to show for his masterful plan except for a long list of casualties. But he had once again failed to break Sherman’s grip on the city.

Battle of Atlanta by Kurz & Allison, ca. 1888. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

As August wore on, while the opposing armies maneuvered outside Atlanta, Sherman initiated a relentless day and night shelling of the city. On August 7 he telegraphed Henry Halleck in Washington, “We keep hammering away here all the time, and there is no peace inside or outside of Atlanta.” But Sherman was far from content solely lobbing shells into Atlanta. His infantry slowly sidled around the city toward the southwest, making sure to keep behind their entrenchments in case the Confederates came bounding forward in another wild attack. But by the end of the month, it was clear to Hood the enemy was moving toward Jonesboro to sever the last remaining rail line into Atlanta, which ran south to Macon. Without the use of that railway the city would be cut off from supply, and Hood moved to thwart the effort.

Federal troops were indeed moving aggressively. On August 30, John Logan’s Fifteenth Corps crossed the Flint River. Logan’s men positioned themselves on “the highest ground” between the river and the railroad tracks. Right behind Logan’s troops, and just across the Flint, were the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Corps. In an effort to stymie the Federal movements, troops from Hardee’s Corps and Lee’s Corps attacked on August 31. By that time Logan’s men had a formidable line of earthworks along their front and for “over two hours” the Rebels made vain efforts to carry the Federal line. When the fighting finally concluded over 400 Rebel dead were left on the field. By nightfall, with the offensive having ground to a halt, Hood ordered Lee back to Atlanta based on reports indicating Sherman might assault the city in the morning. Hood was unaware that he was leaving Hardee to face nearly all of Sherman’s army. The end result was that Hardee was forced to stand alone on September 1. By late afternoon the Fourteenth Corps, commanded by Gen. Jefferson C. Davis, had swept in from the north to support the left of O. O. Howard’s Army of the Tennessee, which was involved in the fighting the day before. At around 4 pm Davis’ troops attacked Hardee’s position. On the northern end of the Rebel line, which was held by Patrick Cleburne’s Division, a salient had been constructed by the troops in Gen. Daniel C. Govan’s Brigade. When Davis’ troops struck this area the fighting swelled and became hand-to-hand in some places.

Hardee’s vastly outnumbered men fought with great desperation, but they were simply no match for the swarms of Union soldiers. When the salient finally ruptured many of the Confederates were trapped. A good number were killed and wounded during the desperate stand, but nearly nine hundred were taken prisoner, including Govan. Seven battle flags and two four-gun batteries were also captured. Only darkness allowed Hardee to quietly slip away. He pulled the men out of their precarious position and marched them south to Lovejoy’s Station, where a new line of entrenchments was hastily erected.

When Hood learned of Hardee’s defeat at Jonesboro he realized the futility of holding Atlanta any longer. With Sherman holding all of the rail lines around the city, it was clear that evacuation was the only option. But Hood’s army was dangerously split. Hardee was on his way to Lovejoy’s Station seven miles south of Jonesboro, A. P. Stewart and G. W. Smith were still inside Atlanta, and S. D. Lee, moving up from Jonesboro, was east of Rough and Ready about six miles south of Atlanta. Lee was halted and ordered to “cover the evacuation of the city.” Then around dusk on September 1, Stewart and Smith swung their men into formation and began moving out of Atlanta, tramping southward along the McDonough Road. Soon all three columns were moving toward Lovejoy’s Station to join William Hardee.

At around 11 am on September 2, the Twentieth Corps of the Army of the Cumberland marched into Atlanta unopposed. That same day, Gen. David S. Stanley’s Fourth Corps, Army of the Cumberland, located Hardee and his troops at around noon just a mile north of Lovejoy’s Station. Plans for an attack were soon underway. Stanley was told by O. O. Howard that troops from the Army of the Tennessee would “advance in concert” with the Fourth Corps, but it was 3:30 pm before Howard was ready to move. It was nearly 6 pm before the Federal troops reached the Confederate position. Luckily for Hardee and his men the pressure was far less than it had been the previous day, and the Southerners were able to repulse the attack. To the north, the sounds of the combat could be heard by the Southern troops who were winding their way down from Atlanta. Not until September 3 did Stewart and Lee arrive at Lovejoy’s Station to relieve Hardee’s battered corps. The final act of the Atlanta Campaign turned out as one-sided as the July battles had been. Rebel losses around Jonesboro were at least 4,000 and Federal casualties amounted to about 1,450.

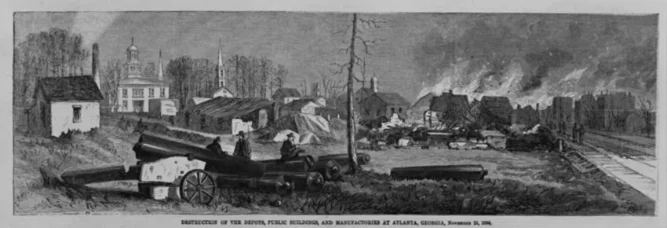

For William Sherman the capture of Atlanta was only part of a much larger picture. For some time the idea of a march to the Atlantic seaboard, through the heart of Georgia, had been on his mind. In a September 4 wire to Henry Halleck, Sherman expressed several ideas and struck at the core of his feelings about war. He said, “I propose to remove all the inhabitants of Atlanta, sending those committed to our cause to the rear, and the rebel families to the front. I will allow no trade, manufactories nor any citizens there at all, so that we will have entire use of the railroad back, as also such corn and forage as may be reached by our troops. If the people raise a howl against my barbarity and cruelty, I will answer that war is war, and not popularity seeking. If they want peace, they and their relatives must stop the war.”

Soon Sherman would be moving across Georgia, and Hood would be headed toward Middle Tennessee, and a little town called Franklin.

When Sherman’s army left Atlanta in November 1864, they destroyed the depots, public buildings, and manufactories. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.