A Century Old Battle

Over fifty-five years ago, the United States embarked on a challenging project: how to remember the 100th anniversary of the Civil War. The government and public were faced with the decision of how to honor the memory of the men who fought and died in the brutal war without anyone present who witnessed it first-hand.

The formation of a national Civil War centennial group was discussed as early as 1953. Combining the efforts of several different organizations, President Eisenhower signed a congressional resolution establishing the U.S. Civil War Centennial Commission in September 1957. The early years of the Commission were filled with controversies and opposing ideas. While trying to determine the nature of the anniversary events and the purpose of the Commission itself, many of the members did not take into consideration the world around them. In a time of racial tension, the leadership of the Commission refused to hear any voices other than their own. The unwillingness to address these issues led to changes, most notably the replacement of the director and chairman in 1961.

One Hundred Years Ago

State and local governments were encouraged to form their own “Centennial Commissions” to coordinate local events. The Tennessee Civil War Centennial Commission was formed in 1959 and began assisting smaller institutions with events, programs and research material. The local Williamson County Commission was headquartered at the Carter House and included nine noted community members.

The Williamson County Centennial Committee coordinated and participated in a variety of activities centered around the Battle of Franklin re-enactment and parade. The Committee also worked to produce a series of Centennial broadcasts with the local radio station WAGG. Together they presented thirty days of radio programming leading up to and including the actual battle anniversary. From November 1-27, daily recorded broadcasts were shared with listeners about Civil War life, the Tennessee Campaign of 1864, and many other related topics. These broadcasts entitled “One Hundred Years Ago,” were written by Commission member Herbert Harper and shared with thousands of listeners. November 28-30, 1964 were filled with live “on-the-spot” broadcasts from the Battle of Franklin re-enactment as well as the McGavock Confederate Cemetery.

Franklin Remembers

The culmination of the Centennial activities in Franklin was the battle re-enactment, held on Sunday, November 29 at 2pm. The event took place at the Kinnard farm on the grounds surrounding Carnton and included the retelling of the story of Tod Carter, his retrieval from the battlefield and return to his home, the Carter House. Tod was portrayed by his great-great-nephew, Carter Conway. The re-enactment was narrated for those watching from the sidelines and ended with choral renditions of “America” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The narrator of the battle re-enactment ended the event by reminding the spectators about the actions of the soldiers 100 years earlier: “Together they did forge the destiny of our nation, the United States of America.”

Franklin Centennial Brochure

Carter Conway, shown on the steps of the Carter House, portrayed Tod Carter.

Original printing plate showing the front of the Battle of Franklin Centennial Re-enactors Medal

Centennial events in Franklin included a parade, Main Street window decorating, radio programs, newspaper features, commemorative trinkets, and the large battle reenactment. All of these contributed to a festive atmosphere in the community. Franklin celebrated the events of 1964 with a great enthusiasm and zeal. An estimated 5,000 spectators attended the battle re-enactment and many participated in other anniversary events.

The Centennial was a time to reflect on what the Civil War was and what it would become in the nation’s collective memory. Was the public going to celebrate or commemorate the events of 100 years ago? Were the events of the Centennial designed to celebrate the Northern victory and keep the Southerners in their place? Or was this a way for some to openly resist the new laws of racial desegregation being enacted across the country? Franklin was not immune to the social issues of the 1960s but decided that the Centennial events in the community would take on a more celebratory feel. Events were more often filled with pageantry and excitement, than somber reflections.

Nashville Banner November 30, 1864

Centennial Style

Re-enactments were very popular during the years of the Civil War Centennial. 1960s costumes, like the one seen here, were worn for secession balls and mock-battles throughout the state.

Re-enactors uniform worn at the Franklin Centennial events

Re-enactors prepare to march in the Franklin parade

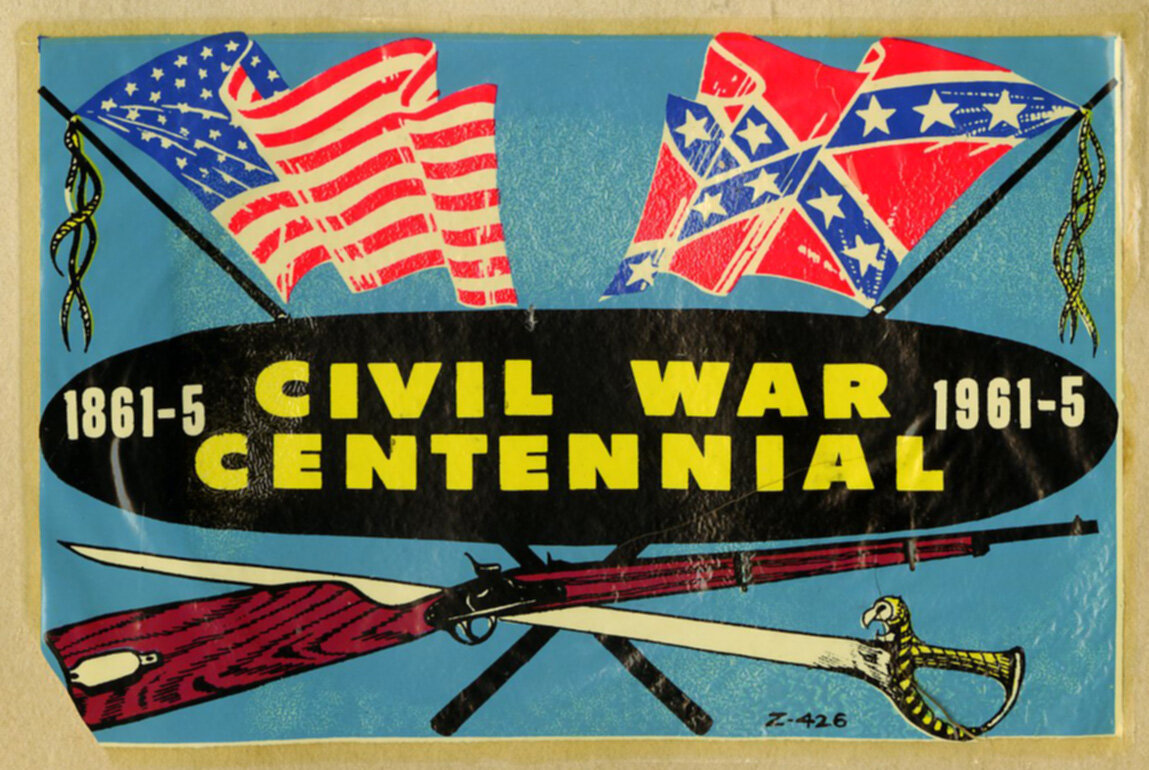

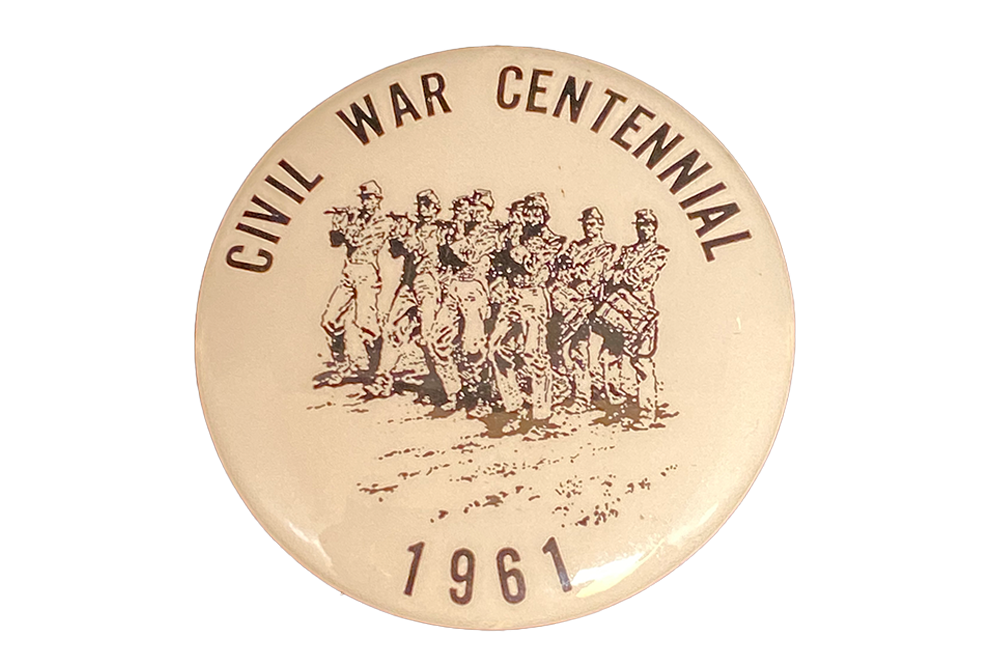

Souvenirs

The Civil War Centennial was a marketing opportunity for many different companies to tap into a thriving market for souvenirs, trinkets, toys, and other memorabilia. The 1960s’ style was reflected in the Centennial merchandise and makes it a unique glimpse into that time in American history.