Coming Home

It is difficult to try and understand the personal struggles of the men returning home after the American Civil War.

Soldiers faced obstacles on all fronts. Southerners were forced to reconcile their life and sacrifice with an effort for independence that failed. Northerners were forced to weigh the sacrifice they made in their successful effort to preserve the Union. Soldiers from both sides were confronted with the home-front realities all soldiers returning from war face: loving families and communities, but few who could relate to what they experienced. Returning to their previous lives, whether on the farm or in the city, was the only option for most of the men. As with many veterans today, special groups were formed. This allowed the Civil War Veterans to talk to other men who had shared similar experiences and gone through a time that was truly inexplicable to those around them.

“There was a feeling of relief that the war was at last over; that we were at liberty to go home once more…The feeling of relief was so great that for a time all else was forgotten in the satisfaction that gave. We now began our preparations in earnest for our return home. When the prospect was in view every moment lost, seemed an age.” - excerpt from the diary of James L. Cooper, April 1865

James L. Cooper

Frock Coat of James L. Cooper worn at the Battle of Franklin

Comradeship

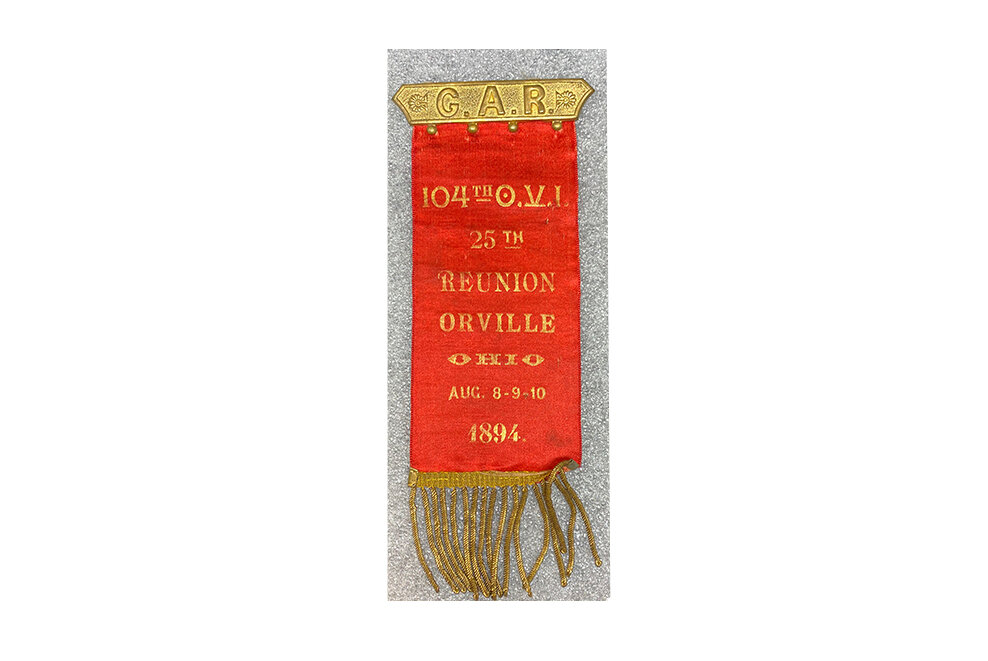

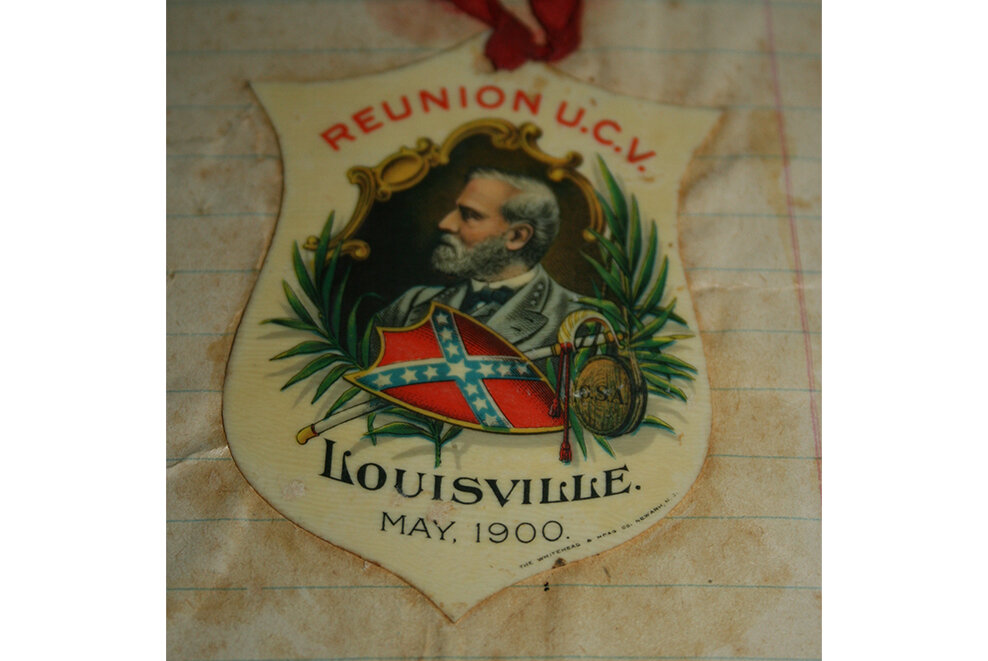

Two main organizations for veterans were established in the U.S. after the war: The United Confederate Veterans (U.C.V.) and the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.). These two organizations had national publications, held reunions, and worked to get veterans compensation for their service and, in some cases, their injuries. In 1866, the G.A.R., the Union veterans’ organization was formed in Decatur, Illinois. Many veterans’ organizations sprang up throughout the Southern States and in 1889 the U.C.V. was formed in New Orleans. This organization took the place of many smaller and disorganized groups and began holding regularly scheduled conventions and reunions. Both the G.A.R. and U.C.V. were founded to remember fallen comrades, provide aid for widows and orphans, and assist disabled veterans. Men who joined the organizations were able to spend time with others who understood them and assist those in need.

Throughout the years these groups were a platform for charity work, as well as a political network. Both the G.A.R. and the U.C.V. wielded political power in their respective regions. Men were rarely elected without the backing and support of these groups into the early 20th century. At its height, the G.A.R. had over 490,000 members; smaller, but no less active, the U.C.V. had a membership of over 160,000.

The Confederate Veteran Magazine was a monthly Nashville based publication from 1893 to 1932. The magazine included letters and editorials submitted by former Confederates. A popular magazine in its time, it is a fascinating resource for modern historians.

In the years following the war, veterans battled with the pen in publications like Confederate Veteran Magazine, The National Tribune, and locally published newsletters. Former comrades discussed and debated everything from causes of the war to regimental positions in battle. Many of the men who experienced these things first-hand were never able to come to an agreement as to what truly happened. The modern debate continues with the echoes of 150 years behind it.

Reunions

The U.C.V. and G.A.R. held reunions and conventions in all areas of the country but focused heavily on battle sites. The first documented reunion held in Franklin was the 1877 reunion of the 20th Tennessee Infantry. Regional reunions, although not officially sponsored by the G.A.R. or U.C.V., were held in Franklin until 1927, the largest reunion drawing over 12,000 people in 1892. Parades, picnics, speeches, and battlefield tours were part of the events. By the early part of the 20th century, survivors were dwindling in number. The final reunion was held in Franklin in 1927, with 250 delegates in attendance.

1877 Reunion of the 20th Tennessee held in McGavock's Grove

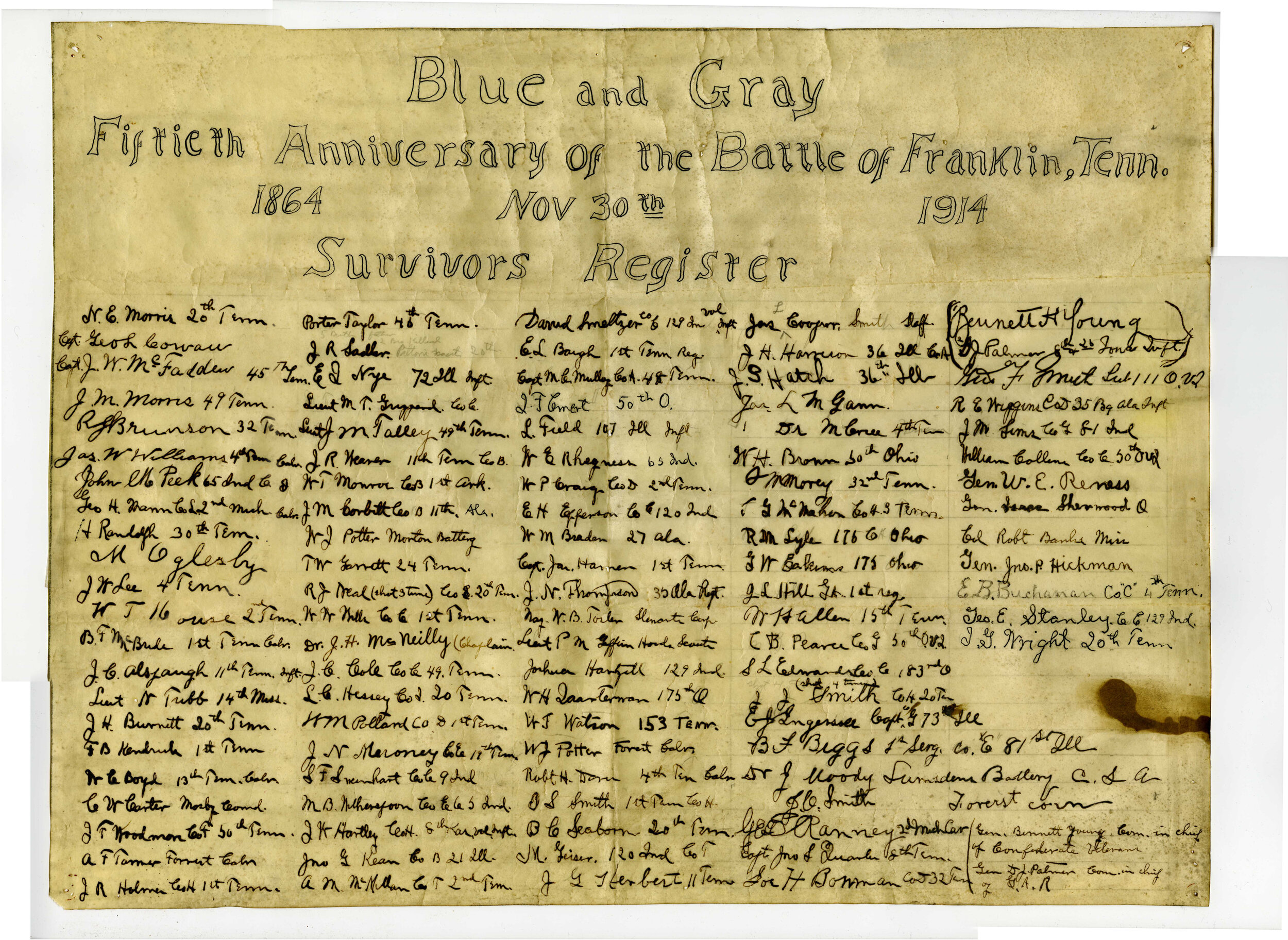

The 50th anniversary celebration of the Battle of Franklin was held in 1914 as a Blue and Gray Reunion; former enemies walked the ground together and remembered the events of November 30, 1864. The badge, produced for attendees of the event, showed the true feelings of those in attendance: “Whether blue or gray it makes no difference to us. We are friends and brothers now.”

When we talk about the American Civil War, we often focus on the terrible loss of life. And while that was a horrific part of the story, many people do not consider what it was like for the survivors after the battles and after the war was over. These veterans’ groups helped thousands of men cope with what they had experienced.

Memory

Shaped by the words of veterans, the study of the Civil War has spanned 150 years. Each generation has viewed the implications of the war differently, and with innumerable books on the subject, each subsequent generation will as well. As those in the modern world struggle to understand the events of so many years ago, we in turn struggle to understand the world around us and how these events have shaped us.