To Save the Union: The Election of 1864

by Eric A. Jacobson

Presidential elections have been part of the American experiment since 1789, but not all have carried the same weight. Some elections have occurred at critical moments in our history. One of the first such elections was in 1800 when John Adams and Thomas Jefferson engaged in a bitterly divided contest from which Jefferson eventually emerged victorious. In 1828, when Andrew Jackson defeated John Quincy Adams, the country had its first President who was not part of the Virginia or Massachusetts establishment. The 1876 election of Rutherford B. Hayes over Samuel Tilden, which was rife with voter fraud and a divided popular and electoral vote, brought an end to Reconstruction.

In more recent times, the election of 1960 was a watershed moment when John F. Kennedy defeated Richard Nixon and ushered in a new era of American politics. The election of 1968 was one of the most raucous and important since the American Civil War. President Lyndon Johnson refused to run for a second term, and the election was thrown into chaos as the country grappled with Vietnam, Civil Rights, and the long fight against communism. Eventually Nixon emerged victorious over multiple candidates, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, only to be self-destroyed by Watergate years later.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter and moved the country in a materially different direction. The impact of Reagan’s election, and subsequent re-election, cannot be overstated. The 2000 election of George W. Bush over Al Gore, in another bitter contest reminiscent of 1800, had long reaching ramifications far outside the United States. Finally, the election of Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in 2016 was an election that historians will study and write about endlessly in the future.

But perhaps the most important Presidential election in our history was the one held in the autumn of 1864 – in the midst of our civil war.

George Brinton McClellan had once been at the pinnacle of military success. Chosen by President Abraham Lincoln to lead all U.S. forces in the early stages of the war, McClellan suffered one defeat after another, and offered one excuse after another, until he was removed from command in late 1862.

Less than two years later, in August 1864, McClellan, who had once referred to Lincoln as a “well-meaning baboon,” was chosen by the Democrats as their nominee for President of the United States. McClellan had long bristled at Lincoln’s war policies, specifically regarding slavery and the rights of Southern civilians, and thus his choice by the Democrats was not altogether surprising. His running mate was George Pendleton, who was a Copperhead Democrat leader and supported peace with the Confederate States. As the Democratic nominee, McClellan embraced that same position and prepared to unseat Lincoln.

Two months earlier the Republican Party had nominated Lincoln to run for a second term as President. His running mate was Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, who was the only U.S. Senator from a Southern state to not resign his seat when his state seceded. The decision to drop Hannibal Hamlin (the sitting Vice-President) and go with Johnson as the new VP nominee was itself a move that also made the 1864 election incredibly important.

President Lincoln with Gen. George B. McClellan in Antietam, Maryland, 1862.

The summer of 1864 was not an easy time for the Lincoln administration. Those in and around the White House knew of the deep divisions and war weariness that existed in the Northern states. They knew many were unhappy with Lincoln’s decision to release the Emancipation Proclamation a year and a half earlier. Many Northerners were simply exhausted and ready to give up. Lincoln himself had grave doubts about his ability to win the upcoming election.

On August 23, 1864, President Lincoln composed a short memo that he asked several members of his Cabinet to sign without allowing them to read the text. Secretary of State William Seward, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles endorsed the memo as did Attorney General Edward Bates. Almost 160 years after it was written, it puts into clear context how important the upcoming election truly was:

“This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterwards.”

Lincoln was almost certainly correct. The McClellan candidacy, and the platform of the Democratic party, was a “reestablishment of the Union, in all its integrity…and must continue to be the indispensable condition in any settlement.” In addition, it was said that “when any one State is willing to return to the Union it should be received at once with a full guarantee of all its constitutional rights.”

This plea for peace as some Democrats referred to it was, in fact, nothing of the sort. The politics of slavery and its expansion had led directly to secession and war. After so much death and destruction, it seemed incomprehensible to Lincoln and many Northerners that the Union might be preserved with slavery still intact. The result? The move to emancipation and the destruction of slavery. Abolitionists, of course, had long argued for such a course, and Lincoln had spoken repeatedly about the wrongs of slavery and how it conflicted with the Declaration of Independence.

Therefore, in the late summer of 1864, the Democrats of the North, composed of many people with the same sentiments as Democrats of the South, had propped up, of all things, a former United States general officer to run for President. McClellan’s goal – to restore the Union with slavery intact, reject the Emancipation Proclamation, and try to sell the idea that the 600,000 who had already died could somehow be explained away. But he had a bigger problem. In his acceptance letter he said:

“A vast majority of our people, whether in the army and navy or at home, would, as I would, hail with unbounded joy the permanent restoration of peace on the basis of the Union under the Constitution, without the effusion of another drop of blood, but no peace can be permanent without Union.”

Political cartoon illustrating the party platforms in 1864

He could not have been more incorrect. Those serving in the U.S. armed forces were about to revolt and reject both him and the Democrats.

Barely a week after Lincoln had composed his secret memo, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman and his troops captured Atlanta. Like the fall of Nashville, the capture of Vicksburg, and the defeat at Gettysburg, the loss of Atlanta was devastating to the cause of Southern independence. It also helped reassure a fatigued Northern populace, and specifically Republicans, that the war could be won.

On November 8, 1864, Abraham Lincoln crushed George McClellan. Lincoln received 2.2 million votes to 1.81 million for McClellan. However, the electoral vote was complete devastation – 212 to 21. Among the states Lincoln carried 22 of 25. In fact, Lincoln also won elections that were held in Tennessee and Louisiana, as those states had already begun the processes necessary to rejoin the Union. However, because of constitutional issues those votes were invalidated.

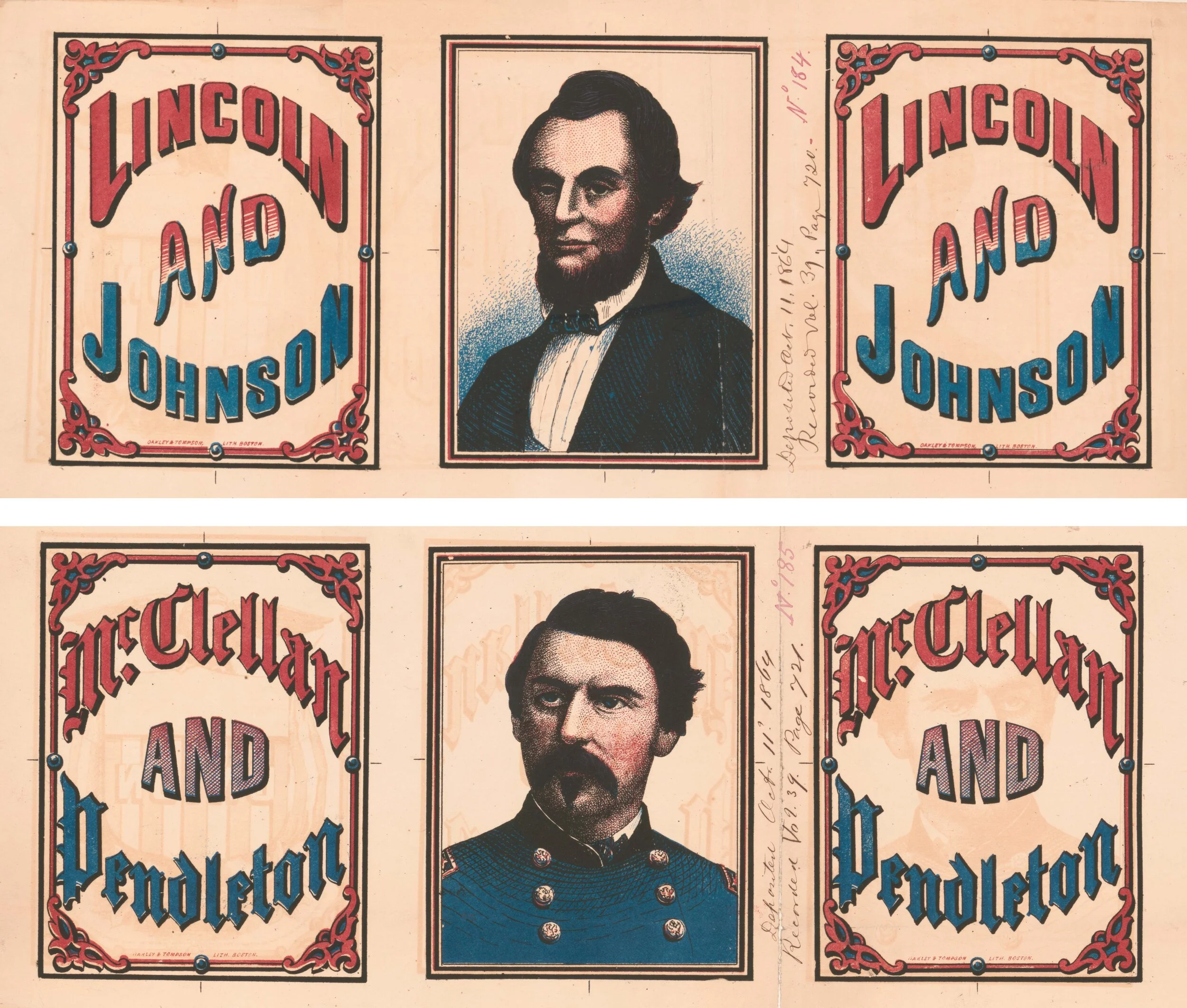

Campaign promotional materials for Lincoln and McClellan.

In the end, it was the soldiers who helped deliver a crushing defeat to McClellan. Nearly three-fourths of them – those who had borne the worst of wartime burdens – voted for Abraham Lincoln and sent a loud and clear message to McClellan and his supporters. The war, while it had been commenced to preserve the Union, was by late 1864, a war to also end slavery, and they were committed to see those dual goals brought to their rightful conclusion. They steadfastly supported their commander-in-chief and steeled themselves for the final push. Within a few months the war finally ended.

It is impossible to know what would have happened had George McClellan won the 1864 election. But there is no guarantee that rebellious Southern states would have ever returned to the Union. Why would they? McClellan was willing to allow slavery to continue. With such a policy on the table, there was no real reason for any state to back off its stance of separation. Moreover, some states might have rejoined, and others might have refused. If they, or any, did not rejoin, would McClellan have fought to force them back in? Certainly not, because that was Lincoln’s policy. Either way, the McClellan/Democrat policy was to return to the status quo and do nothing to prevent the existence of slavery.

Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party, along with over 2 million soldiers, helped to save the United States of America, and they ended slavery through constitutional means. However, Lincoln was gone by the time the 13th Amendment was ratified. His assassination left a void that was impossible to fill. Andrew Johnson was certainly not up to the task, and his Presidency was marred by almost constant struggles with Congress and ultimately impeachment.

Grant campaign button.

In the fall of 1868, Ulysses S. Grant was elected President. He served two terms and worked diligently to fulfill promises that had been made, especially to the formerly enslaved. He also worked in Lincoln’s shadow, knowing as well as anyone what Lincoln wanted and what he might have done and how he might have reacted. But Grant also knew realities that Lincoln might have never anticipated, such as the increasing racial friction and spasms of violence inflicted by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. Lincoln’s plan of conciliatory measures did not seem as palatable to many by the late 1860s.

In the end, there is only so much individual people can do. They do what they can while they have the opportunity. In the fall of 1864, the choice for President came down to two people. History shows that the American electorate chose the man who saved the Union and ended slavery.